The Logic of US Foreign Policy

Published: May 2018

Updated: February 2022

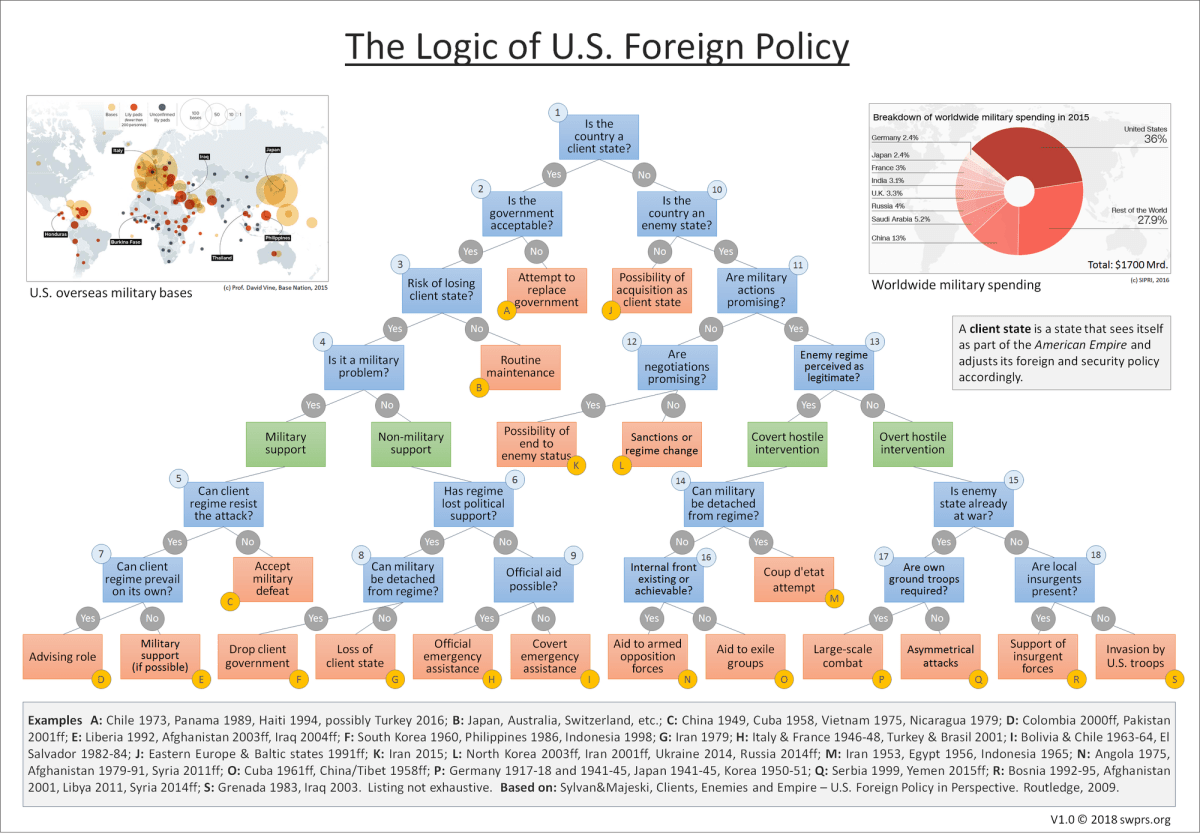

How can US foreign policy be explained in a systematic and rational way? The following chart – based on a model developed by political science professors David Sylvan and Stephen Majeski – reveals the longstanding imperial logic behind US diplomatic and military interventions around the globe.

Due to its economic and military supremacy, the Unites States has been assuming the role of a modern empire since the Second World War and especially since 1990. This status implies a very specific, and a genuinely imperial, logic of action for its foreign policy (see figure above).

The central distinction (#1 in the figure above) from the perspective of an empire is that between client and non-client states. The concept of the client state dates back to the time of the Roman Empire and denotes states that are basically self-governing but nevertheless align their foreign and security policy and their succession of government with the empire.

In the case of existing client states (left side of the diagram), the empire has to decide between routine administration (B – e.g. Switzerland and Austria), military or non-military (e.g. economic) support (D to I – e.g. Colombia and Pakistan), or an attempt to replace unacceptable client governments democratically or militarily (A – e.g. Greece 1967, Chile 1973). In certain cases, a client government can no longer hold on to power despite imperial support and must be dropped or the client state has to be abandoned altogether (C, F, G – e.g. South Vietnam 1975 or Iran 1979).

In the case of non-client states (right side of diagram), the situation is quite different. If a region newly comes into the empire’s sphere of influence, the empire will first attempt to acquire its members peacefully as client states (J). This was the case, e.g., in Eastern Europe and the Baltic States after 1990.

The eastern expansion of NATO (CFR/NATO)

If, on the other hand, a state refuses to become a client state, it sooner or later becomes an enemy state. This is because, solely through its independence and autonomy, it calls into question the empire’s claim to hegemony and thus is threatening its internal and external stability, as an empire that can no longer assert its hegemony will fall apart. In this way, most empires slide into an almost unavoidable compulsion to expand, which in the end will affect even fundamentally peaceful states.

In case of enemy states, the empire must first decide whether military action is promising or not (#11). If not, the empire will possibly start negotiations and, depending on the chances of success, either end the enemy status (K) or impose sanctions or strive for a (civilian) regime change (L).

Typical examples of this situation are currently Iran, North Korea, Russia and increasingly China. It is no coincidence that most of these states possess or are striving for nuclear weapons, because only in this way can the decisive switch #11 be shifted permanently from military to non-military scenarios. Another important factor is the availability of essential raw materials such as oil and gas, as without them it will not be possible to maintain independence in the long term.

The primary concern with raw materials, therefore, is not that the empire wants to own them directly – after all, even enemy states such as the former USSR, modern Russia, Iran, Libya or Venezuela have always sold their raw materials to the West – but that raw materials give enemy states independence and influence, which in itself constitutes a threat from an imperial and hegemonic perspective.

If, on the other hand, the empire judges a military action as promising, the next question is whether or not the enemy state or its government has international legitimacy (#13). If yes, a covert hostile intervention has to be prepared, if no, an overt hostile intervention is possible. In many cases, their autocratic form of government can be used to deny enemy states international legitimacy.

Libya and Syria/Lebanon were the last Mediterranean countries that were not members of NATO’s Mediterranean Partnership (red) and instead wanted to pursue their own regional policy. (NATO)

Covert hostile interventions include, in particular, a coup d’état (M – e.g. Iran 1953, Egypt 1956) and covert support for rebels (N – e.g. Afghanistan 1979ff) or exile groups (O – e.g. Cuba 1961ff). These are, in general, classic intelligence operations.

In the case of overt hostile interventions, the first step is to determine if an enemy state is already engaged in a conflict, if local insurgents are present, and if own ground troops are required. Possible results include asymmetric (air) attacks (Q – e.g. Serbia 1999), support for rebels (R – e.g. Syria 2011ff), a targeted invasion (S – e.g. Iraq 2003), or a full-scale war (P – e.g. Germany 1941-45, Korea 1950-51).

The imperial logic is fundamentally independent of the respective US government. However, different governments may come to different conclusions regarding the prospects of success of military action (#11) and diplomatic negotiations (#12), the advantages of overt versus covert operations (#13), the acceptance of existing client regimes (#2), and domestic political support for military intervention (E).

The logic described above also implies the key geopolitical functions of imperially oriented media, viz. the delegitimization of enemy states or their governments (#13), the support of overt and the concealment of covert hostile operations (#14 to #18), the justification of sanctions and regime changes (L), as well as assisting imperial leadership (B) and the deposition of unwanted client regimes (A).

It is important to note, however, that the rapidly growing range of independent media outlets available on the Internet makes a coherent media portrayal of imperial interventions increasingly difficult. This is a rather new development whose effects on imperial policy are not yet fully predictable.

Video: Retired U.S. General Wesley Clark about the “seven countries in five years” strategy (2007)

Traditional Explanations

The Logic of US Foreign Policy by Sylvan and Majeski offers a consistent explanation for American interventions of the past several decades. The usual explanations – by proponents as well as opponents of these wars – are, however, mostly to be seen as pretexts, rationalizations or at best partial aspects, as the following overview shows.

- Defending democracy and human rights: This classical justification is not very convincing, since democratic governments have been overthrown (A, M, N), autocrats have been supported (E and I), human rights and international law have been violated or violations tolerated by the US.

- Combating terrorism: Paramilitary groups – including Islamist organizations – have been used for decades by the US to eliminate opposing regimes (N and R).

- Specific threats or aggressions against the US: In retrospect, most of these scenarios turned out to be incorrect or made-up (#13; e.g. Tonkin, incubator and WMD claims).

- Raw materials (especially oil and gas): Even enemy states generally want to sell their raw materials to the West, but are prevented from doing so by means of sanctions or war. This is because from an imperial point of view, their independence and influence is seen as a threat.

- Was the Iraq war about oil? Hardly. Already prior to 2003, Iraq had supplied its oil mainly to the West; the Iraqi oil sector was not privatized after the war, and production licences were also issued to corporations in France, Russia and China (which opposed the war).

- Was the Syrian war about natural gas pipelines? No (see here and here). The plans for regime change and war against geopolitically independent Syria had existed for decades and were to be implemented during the so-called “Arab Spring”. (See also a comment by the Syrian president).

- Was the Afghanistan war about a natural gas pipeline? No. The Taliban were and are interested in the TAPI pipeline, but didn’t accept US political and military demands.

- Was the Libya war about oil reserves? No. Libya was already one of Europe’s most important suppliers of oil under Gaddafi, and security of supply has declined significantly since the war. Libya, however, pursued an independent and comprehensive Africa policy – financed by its oil wealth – which collided with the plans of the US and France.

- Was the Iranian regime change in 1953 about the nationalization of oil? No. The US tried to mediate in the British-Iranian oil dispute and urged the British to compromise. Only when Iranian Prime Minister Mossadegh cooperated with the Communist Tudeh Party and opened the country to the Soviet Union did the CIA intervene. Iranian oil, however, remained nationalized even after the coup.

- What was the 2019 Venezuela coup attempt about? See Venezuela: It’s Not About Oil.

- Could renewable energies solve the raw materials problem? Hardly, because renewable energies, storage technologies and high-tech electronics require rare-earth metals, 97% of which are currently produced by China, and conflict minerals such as coltan from the Congo.

- The “Petro-Dollar”: The petro-dollar thesis was developed in the course of the Iraq war. However, the significance of the US dollar does not derive from oil, but from US economic power. While many states naturally prefer the stable dollar for their raw material exports, enemy states often have to switch to other currencies in order to circumvent sanctions (L, e.g. Iran).

- Capitalism: In 1917 Lenin described “imperialism as the highest stage of capitalism,” since capitalist states would have to conquer markets for their overproduction. However, even enemy states want to trade with the West, but are prevented from doing so by sanctions or war. Moreover, pre-capitalist states like Rome and Spain and even anti-capitalist states like the Soviet Union had already waged imperial wars.

- National debt: The national debt is also no reason for US wars, as the US is creating its own money by using the Fed. Moreover, wars themselves contribute immensely to national expenses.

- Arms industry: In 1961 US President Eisenhower warned of the increasing influence of the “military-industrial complex”. The latter is certainly one of the main profiteers of wars, but this applies as well to countries such as Russia, China, Sweden and Switzerland. Moreover, US wars are not arbitrary, but follow a certain logic; after all, even the Roman Empire did not conduct its wars merely to produce as many weapons as possible.

- The “Israel Lobby”: This aspect was emphasized in the book of the same name by Professors Walt and Mearsheimer. The Israeli government and pro-Israeli organizations such as AIPAC lobbied for the 2003 Iraq War and a war against Iran. As a hegemonic power, however, the US must intervene from East Asia to Central Africa and South America, and even the wars in the Middle East follow a superordinate logic. (More: The “Israel Lobby”: Facts and Myths)

- Neoconservatives: Another hypothesis proposes that US wars are driven by the so-called neoconservatives. This idea is disconfirmed, for instance, by the numerous wars initiated or continued by the liberal Clinton and Obama administrations (Yugoslavia, Somalia, Syria, Yemen, etc.)

»We’ve got about five or ten years to clean up those old Soviet client regimes

– Syria, Iran, Iraq – before the next great superpower comes on to challenge us.«

Pentagon policy chief Paul Wolfowitz to General Wesley Clark in 1991 (FORA)

Literature

Sylvan, David & Majeski, Stephen (2009): U.S. Foreign Policy in Perspective: Clients, Enemies and Empire. Routledge, London.

Blum, William (2014): US Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II – Updated Edition. ZED Books, London.

Brzezinski, Zbigniew (1998): The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy And Its Geostrategic Imperatives. Basic Books, New York.

Haass, Richard (2017): A World in Disarray: American Foreign Policy and the Crisis of the Old Order. Penguin Press, London.

Kagan, Robert (1998): The Benevolent Empire. Foreign Policy Magazine.

Kissinger, Henry (2015): World Order. Penguin Books, London.

See also

- Rwanda: What Did Really Happen in 1994?

- Propaganda in the War on Yugoslavia

- The American Empire and its Media