Should Ukraine Accept Putin’s Terms of Peace?

Outrage. That seems to be the emotion driving current policy towards Russia, replacing in a moment the Fear that had dominated Covid policymaking in the past two years. And rightly so, you might say. Putin has just invaded a sovereign nation for no other reason (if he is to be believed) than to take territory off it and impose an unwanted political neutrality upon it. But while outrage is an understandable emotional response, a justified one even, it is not a sound way to approach grave questions of war, peace and national security.

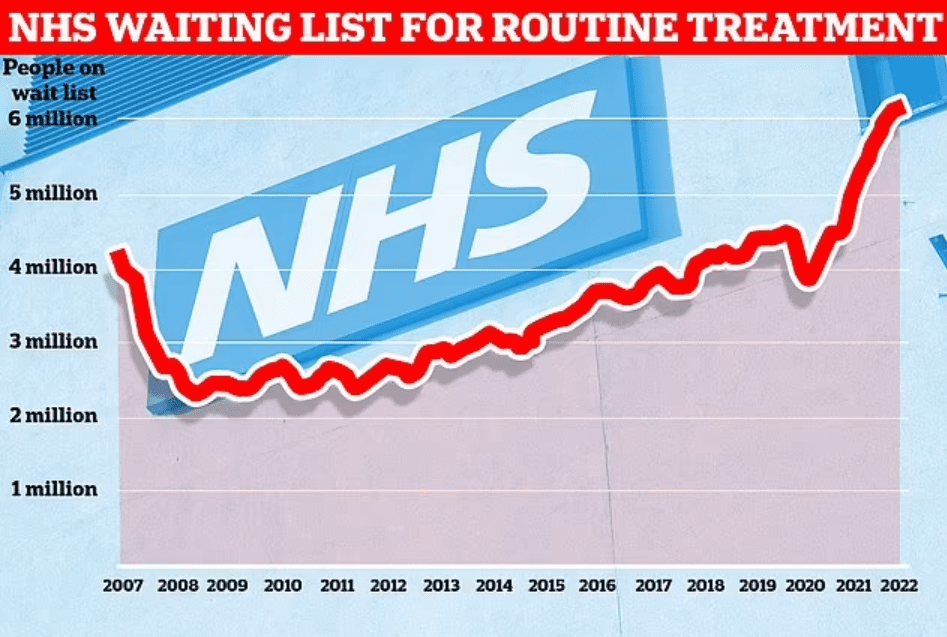

Our leaders ramp up the sanctions, doing severe harm to our own economies already reeling after two years of extreme responses to the pandemic. The cost of energy keeps on going higher and that’s before Putin has followed through on his threat (let’s assume he doesn’t make idle ones) to cut off the gas. This is despite the fact that the West is not at war with Russia, nor is Russia even at war with a Western ally. Why are we imposing such high costs on ourselves to rally to the defence of a country that we hadn’t troubled ourselves formally to ally with? The answer, it seems, is outrage. The costs we are imposing on ourselves will far exceed the costs of other recent conflicts, certainly in terms of broad social and economic impact, creating severe cost-of-living problems for large parts of society. Which might be fine if we were at war, but we are not. Let’s not forget that the reason we hadn’t allied ourselves with Ukraine is precisely because we didn’t want to get involved in a war with Russia. Have we abandoned that important geopolitical goal?

If media sources are to be believed, the Russian incursion has not gone as well as the invaders had hoped and they have suffered significant losses. Nonetheless, there can be little doubt that the Russian armed forces are laying waste to large parts of the country, killing many people and doing damage the low income nation can scarcely afford and which will take years to repair.

The Russians have now reiterated their war aims, which are the terms on which they say they would end the invasion. They should surprise no one who has been paying attention to what they have been saying since the start. The Russians want Ukraine to recognise Russian control of Crimea and the independence of the eastern pro-Russia regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, plus (perhaps most importantly) a constitutional change which commits Ukraine to be neutral and not join the EU or NATO. They have said they recognise that Ukraine is an independent state and appear to have dropped the aim to “de-Nazify” the country.

The response to these demands so far seems to be that they are unacceptable, and Ukraine must be free to make alliances as it sees fit. This means that Russia will continue to wage its war, continue to inflict substantial damage on the country and its people, and Western economies will continue to suffer, alongside Russia’s, as the war continues.

Russia isn’t (it says) trying to take control of the country (it’s not clear that it could) or impose a pro-Russia puppet Government. It isn’t even trying to take direct control of more Ukrainian territory than it already has. It just says it wants a formal constitutional commitment that Ukraine will remain a neutral border state not allied with its de facto ‘enemies’, and recognition of the independence of two eastern regions and its earlier annexation of Crimea.

This hardly seems an unreasonable price for peace – peace that is obviously to everyone’s benefit. The problem is that Western leaders seem to have become committed to the idea that Putin must be seen to fail completely in his illegal war. Given that we are not actually involved in this war, at least in the traditional, military sense, this is a very tricky aim to have, as it implies that despite not fighting the war we are committed psychologically and politically to Putin losing. If that really is our aim, then really we should enter the war properly and actually do what is necessary to bring it about. But we are not willing to do that, because we know that a direct conflict with Russia could get very nasty for us indeed. So instead we expect Ukraine to fight Russia alone, despite being vastly outnumbered, while we supply arms and sanction and boycott Russia to try to bring its economy to its knees.

A significant problem, however, is that many of the sanctions and boycotts appear to be doing at least as much damage to the West as they are to Russia, whose economy is largely insulated from Western action (though perhaps not as much as Putin had hoped).

Since we are inflicting so much harm on our own economies for the sake of a country that is not formally an ally, one question is what will we have left to defend ourselves and our allies should we be attacked?

Outrage appears to forbid this kind of question – fortified by a sense that Putin must not get away with it. His aggression must not be rewarded. I share these sentiments, of course. But they are in the end sentiments, not hard-headed considerations of national security or what is most likely to achieve and maintain peace.

Some have argued that Putin must be stopped now or he will only keep going. But in fact, his ambitions in Ukraine appear to be relatively modest, restricting himself largely to insisting on it being a neutral neighbour. Maybe we don’t believe him, but then if that was how we felt we should have included countries like Ukraine in NATO years ago. There is no indication that Putin will risk attacking a NATO country; he isn’t even (he says) trying to take direct control of more Ukrainian territory or install a puppet government.

The West is powerful but it is not almighty. Defeats in Afghanistan, Syria, Vietnam and elsewhere over the years have taught us that. We cannot fight every battle, vanquish every aggressor, topple every dictator, avenge every abuse. Just as we need to restore a proper sense of proportion in public health policy that was lost sight of over the last two years – we can’t prevent every infection and death – so also we need to maintain a proper sense of what our foreign policy can and cannot achieve, and how much we can afford.

Putin has set out his terms. I’m sure he is keen to withdraw from a war that is costing him considerably, but equally he will not want to go back without what he set out to achieve. Can Ukraine and we in the West swallow our outrage and accept his terms? They leave Ukraine largely intact as an independent country, albeit one unable to make alliances with Russia’s geopolitical competitors (or indeed with Russia). The alternative is that Russia continues its devastation of the country while Ukraine hopes to inflict enough losses in the process that Russia eventually gives up; meanwhile, the West continues its self-destructive sanctions in the hope they add to the pressure on Russia to throw in the towel. It’s a very costly and high risk strategy, particularly given Putin has a considerable military, some highly destructive weapons being held in reserve and a strong incentive not to end in failure. The question is, is Ukraine’s future membership of the EU and NATO really worth all this death and destruction in the country, and all this pain for Western economies? It’s hard to see why the West deems this such an important geopolitical goal that it warrants paying such a high price economically. Even for Ukraine, under Russia’s terms the country would retain its independent government and almost all its territory – this wouldn’t seem an existential matter. Is it worth paying such a high price to avoid? Are priorities and costs being properly weighed by Ukraine and the West, or is the response being largely driven by emotion?

The only argument I can see that would potentially justify the response is if it is seen as a precedent that must not be allowed to stand. But since Ukraine is not part of NATO, and there was never any pledge of military support (and none has been given), what precedent is this supposed to be? That major powers will take action if their security concerns are not respected by neighbouring countries? It seems a strange precedent to go to war over, particularly as America (for instance) would expect nothing less for itself. We don’t have to agree that Putin is ‘entitled’ to do this in some ‘moral’ sense; just recognise that he has the military power to insist on it (like America does), and accept it as a cold reality of Great Power politics that we don’t like but is more trouble than it’s worth to change. The idea that Putin is plotting a general imperial project has no basis – he’s not even trying to take direct control of Donetsk and Luhansk, two pro-Russian regions on his border, let alone the whole of Ukraine or any other country. He will also be acutely aware of the cost of military action and any attempt to subdue an unwilling country.

It seems to me the response of Ukraine and the West is being driven primarily by outrage – wholly understandable outrage that I share. But outrage is no basis for cool-headed policymaking, and even less is it a formula for maintaining or restoring peace in international affairs. That requires much harder-headed thinking about what’s actually going on in the geopolitical interests of countries, and how mutually destructive situations can best be resolved with the least amount of harm, particularly to the non-aggressors.