Doing Stuff Without Evidence is the Opposite of the ‘Precautionary Principle’

The biomedical world has an irritating habit of latching onto social science terminology and tossing it around without really understanding what it means. The ‘precautionary principle’ is a good example. This phrase has been around for about 40 years in social scientific and legal studies of regulation.

The concept of the precautionary principle was first developed in relation to public policy on environmental issues but later extended into studies of occupational health and safety and the rollout of innovative technologies more generally.

In the course of the Covid pandemic, it has rolled off a large number of medical tongues but in completely the opposite direction to that established by every other field that makes use of the term.

The precautionary principle has never encouraged the introduction of innovations, programmes or interventions on the basis that they just might do some good.

It is, in fact, a conservative principle that says innovations should not be permitted unless it is established that benefits will be greater than harms. It tells the advocates for innovation that they have to look just as hard for harms as for benefits. If the harms are theoretical, then research must be done to generate evidence about them before the innovation can be considered further.

The best-known example is probably that of genetically modified food crops (GMOs). These first emerged from the lab in the mid-1990s. The basis for GMOs is brilliant science, but the developers had not done sufficient work to establish their impacts on other varieties of the same species, other species, food availability for wildlife, or human health. It was just assumed, with good reason, that genetically modified tomatoes, cotton or maize would be identical to varieties produced by conventional breeding. Many environmental and consumer groups in Europe did not agree. In the absence of evidence that these crops did not present the theoretical risks identified by their critics, they were not allowed onto the market. Their advocates could not show that the risks had been exaggerated or that any harms were outweighed by the benefits.

In many ways, the underlying principle is familiar to clinicians as primum non nocere: the first duty of a doctor is to do no harm. This is incorporated in many regulations surrounding the pharmaceutical and device industries. Safety cannot be assumed but must be demonstrated. Of course, there is an element of proportionality. If a drug is intended to extend the life of terminally ill cancer patients, it may be appropriate to tolerate a higher risk of adverse effects than in an indigestion cure aimed at a mass market.

As might be imagined, the precautionary principle is not popular with would-be innovators, who find that they cannot get their products to market as quickly and cheaply as they would like. The GMO experience eventually led the European Union to clarify its intention that the precautionary principle should provide a pathway to market rather than a barrier. The pharmaceutical industry, in particular, has advocated an ‘innovation principle’, where products would be licensed unless there was substantial evidence of harm. This inverts the precautionary principle in much the same way as some of its medical uses during the pandemic.

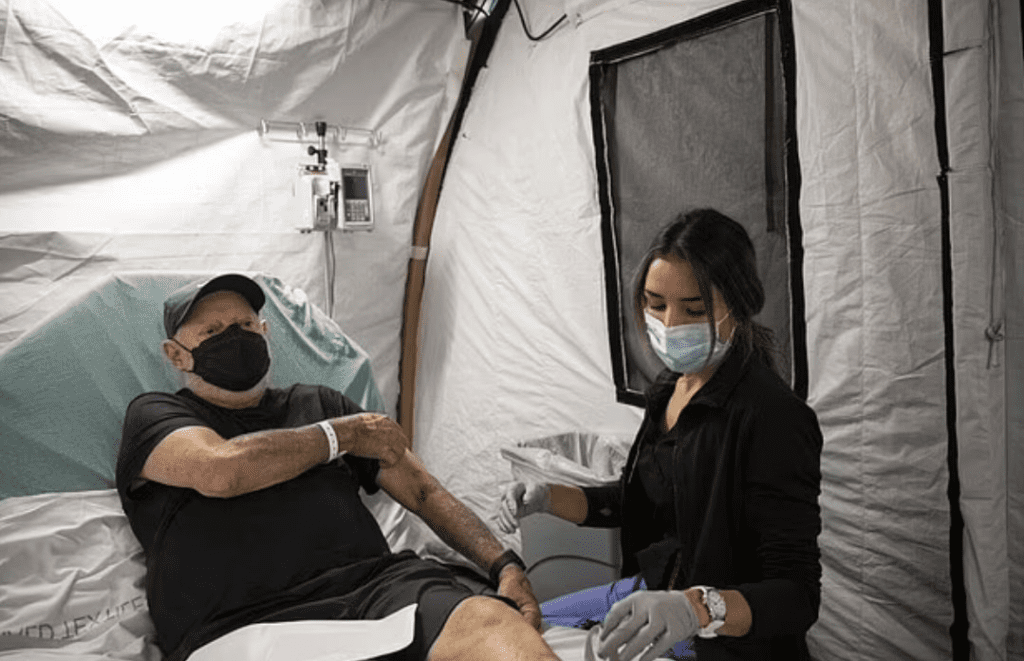

Emergency conditions do not justify the abandonment of the precautionary principle. If action is urgent, but benefits and harms are uncertain, then the actions or innovations must be temporary, provisional and closely monitored with a view to withdrawing or halting them if their benefits are not proportionate to their harms. Doing stuff ‘just in case’ or ‘it might help’ is not sufficient.

Pandemic policies would have looked very different if the precautionary principle had been applied correctly, especially to non-pharmaceutical interventions. These should have been examined with the well-established tools of regulation studies in social science and law to consider their legitimacy, proportionality and effectiveness.

Dr. Robert Dingwall, a former Government adviser on the JCVI and NERVTAG during the COVID-19 pandemic, is Professor of Sociology at Nottingham Trent University and a consulting sociologist, researcher, writer and entrepreneur. This article first appeared on Trust the Evidence.